M-209: History

From B-21 to C-38 (From 1921 to 1938) [0] [1]

|

|

|

| B-21 | C-36 | C-38S |

The B-21

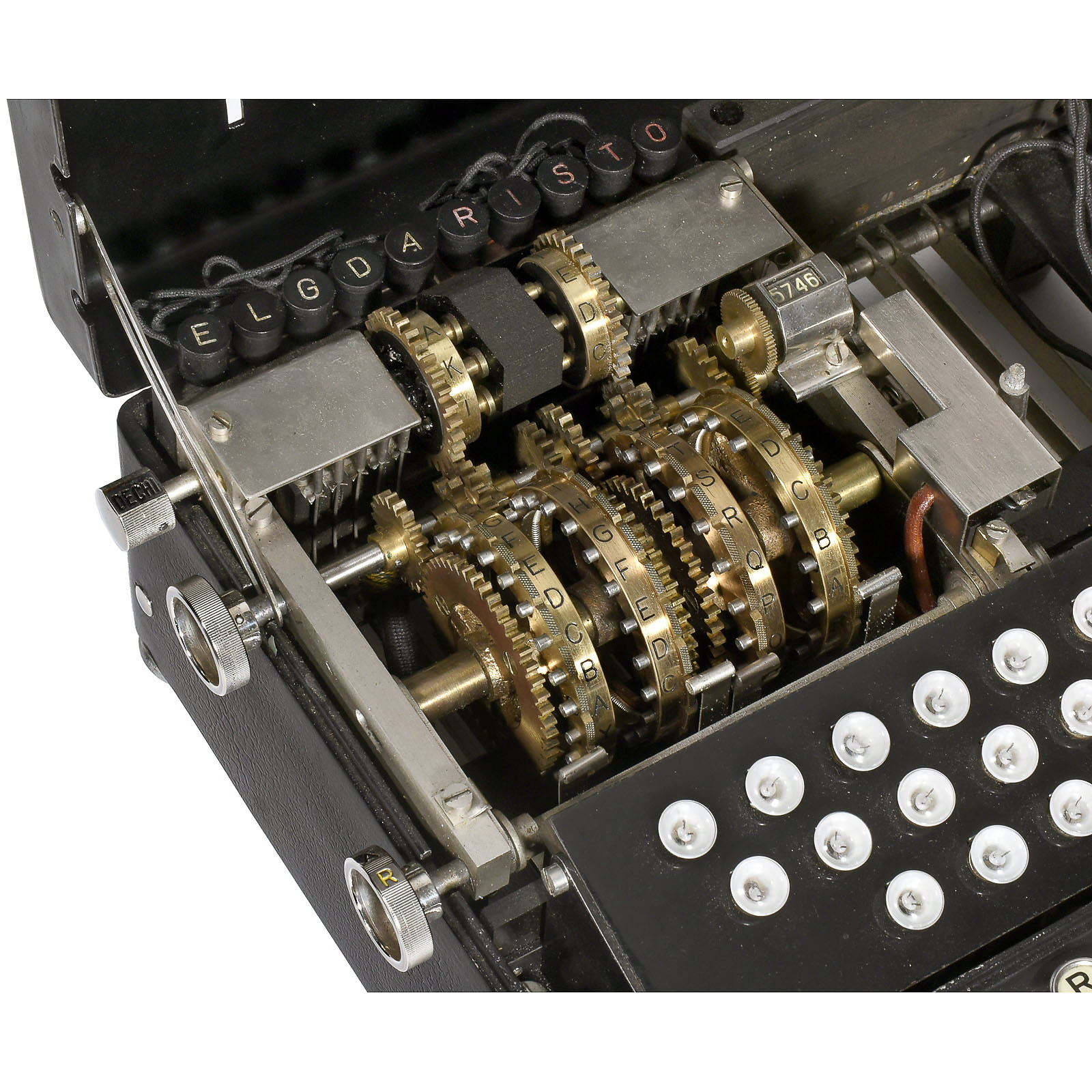

In 1921, Boris Hagelin developed his first cipher machine whilst working for A.B. Cryptograph company in Sweden.The B-21 is a cipher machine which externarly looks like an Enigma. Indeed, by pressing a key, an electric lamp lits up a letter. But, internaly, the machine is completly different. The machine has 2 half-rotors whose stepping is controlled by two separate pairs of pinwheels (keying wheels).

The C-35/C-36 (1935/1936) [15] [16]

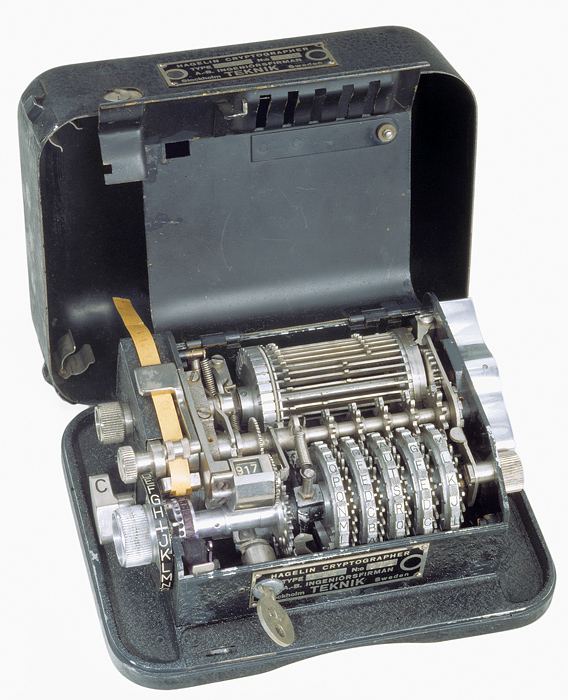

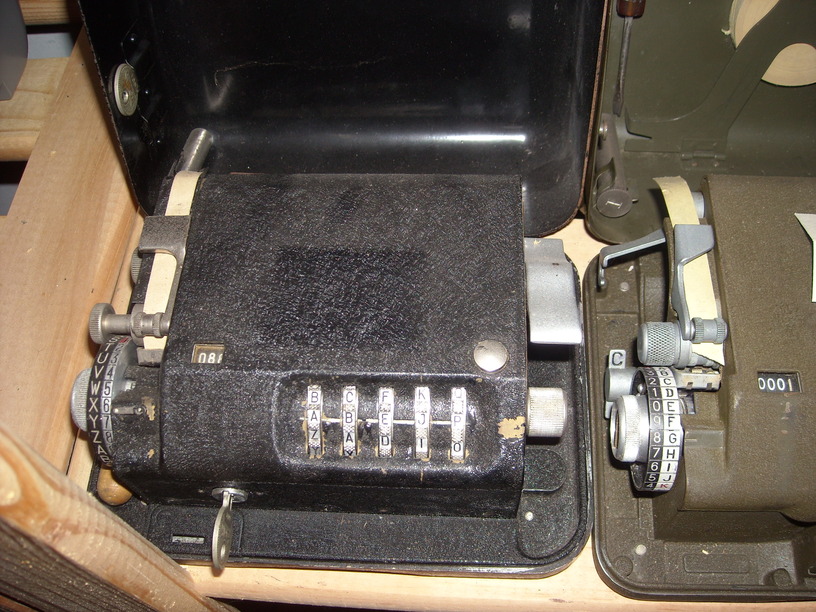

In 1934, The French "Second Bureau" asked Mr Hagelin to design a cipher pocket machine that can print. Mr Hagelin imagined a machine composed of a drum with bars around its circumference that can move and accordingly action a type-wheel. The bars move under control of pinwheels based on those used in the encryption engine B-21.The first model, the C-35, produced in 1935, used a drum with 25 bars and 5 pinwheels. Each wheel has pins around their circumferences, which could be placed in two different positions, either active or inactive. The active pins worked upon the bars of the drum by means of a control arm. The first bar has only one cam in front of the first wheel. If the current pin of this wheel is active, the control arm moves the bar. In front of the second wheel there are two cams. In front of the third wheel there are four cams. In front of the fourth wheel there are eight cams and in front of the last wheel there are ten cams. When the drum was revolved during operation, the control arms pushed their corresponding bars (from 0 to 25 bars) to the left and so engaged the gearwheel connected to the typewheel.

The next year, in 1936, Mr Hagelin produced a second model: the C-36. A protective cover was added. The bottom plate was formed so that the machine could be used in the field strapped over the knee of the operator. In this model, there are respectively 1, 2, 3, 7, 12 cams in front of each keywheel.

For the C-35/C-36, the five wheels have respectively 25, 23, 21, 19 and 17 divisions, which resulted in a period length of 3,900,225 operations.

The C-38 (1938)

Mr Hagelin took the advice of Mr Yves Gylden and improved its C-36 which became C-38 in 1938. First, was added a wheel (with 26 pins). Second, the lugs (the former cams) were no longer set and it was possible to have overlaps. Then on each bar, it was possible to set one or two lugs to active positions (so opposite any of the six wheels). If one sets two lugs, there is an overlap. According to which pins are active, the key will be increased only by one even if the two pins opposite lugs are active. This new feature significantly improves the security of the C models.Contract with U.S. Army

Hagelin initiative [0] [1]

At the beginning of March 1940, Mr Hagelin made a trip to the US on his own initiative to try to sell its C-38 machine to the U.S. Army.Adoption of the Hagelin's machine even against Friedman's advice [2]

As soon as Mr W.F. Friedman became the chief cryptanalyst of War Department, he studied all cryptographic devices which had been invented and produced from around the world. For example, he bought (for War Department) a Kryha machine, several Hebern machines, an Enigma (the commercial version), the Hagelin B-21 and later the C-35. Each time, he studied the security of these inventions and prevented U.S. Army to adopt them.When he studied the C-38, as previously stated, Friedman advised U.S. Army against this machine. Perhaps his judgment was not impartial. Indeed he had designed its own machine, the M-325 (SIGFOY), on the basis of the Enigma, and he wanted this machine to be choosen by the U.S. Army as a tactical encryption means.

He was however obliged to reconized that the security improvements (compared to C-35/C-36) were adequate for a cipher field instrument. Here are its words: "While the machine was by no means perfect, it met a need that could hardly have been fulfilled otherwise".

Finally, U.S. Army adopted the Hagelin's C-38 under the name of M-209 and Navy under the name of CSP-1500. These machines were intented to replace the M-94 and CSP-488.

In the U.S. Army, the M-209 was used as a tactical cipher means in military units division level and below. Conversely, the Sigaba was used at the top levels military hierarchy from Army Corps level.

Production [3]

Americans began with an initial order for 50 machines.Later, Smith-Corona produced it in huge quantities for $64 a copy. One former NSA official estimated that some 125,000 devices were built before it went out of production. The first M-209 machines (M-209-A) produced by Smith-Corona were tagged 1942, in the same way the TM 11-380 (the M-209 manual) which was tagged April 1942.

The C-38 was simplified. For example, the lock was removed. The slide was fixed to 25 (on the previous models, there may be a configurable shift between the indicator disc and the type-wheel). The number of bars on the cage was fixed to 27 (on swedish C-38, there were 29 bars).

|

|

|

| C-38S | M-209 (not A or B) | M-209A with 1942 manual |

World War II

German point of view [4]

Excerpts from TICOM DF-120:"The first use of the machine by the Americans occured in December 1942 in the African theater of war. The messages are recognizable through two 5-letter indicator groups at the beginning of the message of the type AABCD EFGXY, which are repeated at the end of the message.

The first messages in depth, that is, messages with like indicator groups, appeared in January 1943. Since it was a matter of exceptionally long messages of 682 letters, the entry into the entire system succeeded with them. The two messages were linguistically solved and the first internal machine setting found analytically.

When in April and May 1943, the then widely used strip system, known as M-94, was supplanted by this machine, we could read this new traffic currently as long as messages in depth appeared. Thus, messages were solved from the theater of war in Africa, later in Sicily, and Italy, and also from the Anglo-American invasion army which was waiting in England. Here it was maily a question of practice messages, which, nevertheless, were read currently and which gave valuable hints to Evaluation, so that, by the beginning of the invasion, a rather clear picture of the strength and composition of the invasion army had been built up. Since the beginning of the invasion messages mainly from Western front and from Italy are going worked on."

During the war, several M-209, manuals and even key-lists were captured. We know at least these appearances:

- Key-list of June 1943 was captured in Sicily.

- Key-list from 6 to 11 June 1944 (D-day, D-day+1, D-day+2, ... D-day+5) were captured in Normandy.

- Key-list of October, 1944.

Japanese point of view [5]

The Japanese Army had decided in 1943 to recruit graduates in mathematics for work in cryptanalysis. Its interests concentrated on the "strip-cipher" (M-94) and the cipher "M-209". The General Staff of the Japanese Army had bought a prototype of this machine in Sweden before the war. The military engineer Yamamoto guessed that "M-209" was an adaptation of this Swedish prototype. He could even determine the details of the modifications of the prototype that had produced M-209.Japanese cryptanalysts succeeded in breaking M-209, but as the keys were changed daily, they were unable to break it every day.

Note: Setsuo Fukutomi does not say so, but probably the deciphering were allowed through messages in depth.

French troops [6]

All French troops fighting with the Allies received the M-209 since 1943. The TM 11-380 manual was translated in French for them.Philipine [7]

During the Japanese occupation in World War II, there was an extensive Philippine resistance movement, which opposed the Japanese with active underground and guerrilla activity that increased over the years. General MacArthur's Headquarters supplied radios, technical personnel, codes, ciphers, signals operating instructions and even M-94 and M-209 cipher devices for the guerrillas to use.After WWII

TICOM, Korean War [11]

After the end of World War II, US cryptographic agencies investigated through German archives and questionned POW (Prisonner Of War) about German cryptogaphic methods. This organization was called TICOM (Target Intelligence COMmittee). TICOM discovered that German read many M-209 messages because of the carelessness of code clerks. In particular, many messages were sent with same external key. The TM 11-380 (the M-209 manual) used during Korean War formally prohibits the reuse of an external key. Overall, the security measures were much tighter than during WWII. No document published suggests that North Korea could read the U.S. Messages regularly.Nato: M-209 and KL-7[3][14]

Several different systems, including Typex and M-209, were loaned for NATO use, but none of them solved the problem of availability and security. Then in 1953, the JCS (Joint Chiefs of Staff) proposed the brand-new AFSAM-7 (the future KL-7), the best'off-line system the U.S. had. State and CIA both opposed the decision, but after several years of acrimonious disagreement, USCIB approved the AFSAM-7 for transfer to NATO. This machine took office at NATO in 1958.In 1952, NATO authorized M-209 using for third level NATO traffic. The model used was the M-209 with French modification. The following restrictions were applied:

- Key must be changed daily.

- Bisection must be applied on messages before encryption.

- Message length must not to exceed 50 groups (250 letters).

- Spacing must be variable.

|

|

|

French C-36 next to a French/NATO M-209 |

(with modified typewheel) |

M-209 modification [8]

A NSA document, dated on 17 December 1953, states that the M-209 had been modified. Perhaps the American Army adopted the French Army modification. Another hypothesis is that they tried to add a keyboard.Note that the US Army already had a machine with keyboard: the BC-38. It was compatible with M-209 and was designed to be use in Headquarters.

M-209 end of use by US Army [3] [13]

After Korean War, The M-209 was considered by U.S. Army as a difficult and time-consumming cryptographic means to set properly. Nonetheless, it continued to be used until the early 1960. After that, it was removed from service. It was replaced by KY-8 (NESTOR), a voice encryption unit.One legend said that the U.S. government dumped thousands of M-209 into the ocean rather than being sold them as surplus. An alternate legend claims they were first "steam rolled" or torched into junk and then dumped into the ocean.

M-209 and VietNam war [9] [10] [12]

France had provided the South Vietnamese army and police force with M-209s in the 1950s. The South Vietnamese were routinely encrypting 500 five-letter group messages, rather than 500-character messages as required for in the M-209 use. Since their messages were five times too long, cryptographic security vanished. This problem was eliminated only when the NSA representative specifically brought it to the attention of South Vietnamese officials.In mid-1964, the United States supplied itself M-209 cryptomachines to RVN (Republic of VietNam) and ROK (Republic Of Korea) forces for use at battalion level, and in January 1965 it distributed the AN-series operations code for encryption at any echelon (replacing the SLIDEX).

The Falling of Saigon (April 1975).

All current or sensitive equipment and material had been removed or

destroyed by the Americans and South Vietnamese. However, a large

amount of material was lost such as M-209 cipher devices and tactical

secure speech gear such as the KY-8 (Nestor).

|

|

|

| South Vietnam Army Command Officer |

Republic of Vietnam Military Force |

References

-

[0].

THE STORY OF THE HAGELIN CRYPTOS, by Boris C.W. Hagelin,

Cryptologia, July 1994.

- [1]. Crypto Museum - Boris Hagelin, The Story of Hagelin Cryptos

- [2]. NSA - Friedman Documents - Important Contributions to communication security 1939-1945

- [3]. NSA - American Cryptology during the Cold war, 1945-1989

- [4]. Google - TICOM DF-120.

- [5]. Springer - Mathematics and War in Japan, by Setsuo Fukutomi

- [6]. This site - French M-209

- [7]. NSA - The Cryptologic Effort by the Philippine Guerilla Army 1944-1945

- [8]. NSA - NSA Document Release to NARA in April 2011

- [9]. NSA - Remembering the Lesson of the Vietnam War

- [10]. NSA - SOUTHEAST ASIA - Working against the tide

- [11]. This site - TICOM

- [12]. SIGINT and the Falling of Saigon, April 1975

- [13]. Secret Code Machines: The Inside Story, By A.E. Feldman

- [14]. NATO Archives: Acceptation du Converter M-209 avec les modifications françaises (Acceptance of m-209 converter with the French changes) - French version English version

- [15]. Fréd.André: C-36 Hagelin machines

- [16]. Fréd.André: C-35 Patent