Hagelin serie C: Indicators

Excerpts of the TM 11-380:

SOI (1943) Making and managing key listsIntroduction

When a cipher clerk sends a ciphered message to his correspondent, he needs to transmit him every things needed to decipher it. The indicator is a string which contains precisely those informations. It is often placed at the beginning and the end of the message. Sometimes, it is buried inside the message.

When correspondents use several crypto-systems, the indicator must indicate which one was used.

If the crypto-system used is a Hagelin Serie C, the correspondents need to share the same setting of Lugs and Pins (internal key). Usually, these settings are written in a Key List. A key list is valid for a period of time (daily most usually) and for a net (message centers of a particular division or corps). If the net membership isn't obvious (the radio call signs can indicate the net), the indicator must indicate which key net is used (and so which key list is used).

In any case, the indicator must contain for each message the actual external key (the wheel start setting) or an indication of which external key was used.

A smart indicator system is an important element of security. For example, if the indicator contains directly the external key, as soon as we find the internal key (Pins and Lugs setting), we can decipher any encrypted message with it. Worse, it is possible to put messages in depth and so to find Pins and Lugs setting. Therefore, to encrypt the message key is wise.

TM 11-380, 1942

The 11-380 is the manual of M-209 printed by US Army. The 1942 version describes a very simple indicator system (the external key was in plain text).

"The message indicator is selected by the operator himself and determines for each message the initial positions of the six key wheels. It will appear at the beginning and ending of the message. An example of such a message indicator would be HILQD and the wheels would be adjusted so that the letters HHILQD would be lined up along the bench mark."

TM 11-380, 1944

The 1944 version of TM 11-380 describes a more complex indicator system, but the external key is still in plain text. The whole indicator is composed of three parts:

- The system indicator : the crypto-system used ("FW" = M-209).

- The message indicator : the external key (wheels start setting).

- The cipher-key indicator : the key-net used (and then the key-list used)

TM 11-380, 1947

The 1947 version of TM 11-380 describes a very good indicator system with the external key enciphered. Besides, the cipher-key indicator (the key-net) must be omitted each time it is possible (for example if the key-net can be deduced from call signs).

In fact, this indicator method was the most used by US Army during WWII (see below).

Signal Operation Instructions

Even an Operator could create a key list and indicator system with the help of the TM 11-380 manual, it happened rarely. In most cases, the indicator system and key list for a month was written in a document called Signal Operation Instructions (SOI). It also contains the radio call signs. Typically, a SOI version was published for a month period and for a division.

After WWII (in Korean War, for example), an organization (a division for example) is still able to create its own key list, but it must use the indicator method which was previously described in the SOI (in which the message key is enciphered). The TM 11-380 1947 version is very explicit. Anyway, it is forbidden to send in plain text the external key.

The US Navy System

The US Navy indicator system used in World War II (1942), is an enciphered one. To indicate that the cryptosystem CSP-1500 (The Navy name of M-209) is used, the indicator message was borded by two XX, for example XXGTY JUOXX. The whole indicator was put at the beginning of the message and repeated at the end.The message key (the external setting which indicate the start of wheels) is chosen at random. It is devided in three groups of two letters. Each group is ciphered via a table of bigrams which is part of the key list (HAG KEY LIST, 1942).

Usage of the C38m by the Italian Navy during World War II

Rear Admiral Luigi Domini describes this method:It was understood that the greatest danger was in the reuse of the keystream, that is two or more messages enciphered with the same key, within the same month. For this reason this practice was positively forbidden and all authorities issued a C38m were assigned series of keys not to be used by other authorities.

... The second edition (of The Table of External Keys for Cipher Machine), enforced on March 1, 1942, contained 15,000 normal keys plus 3,000 for the R.P. Messages (Restricted-Personal).

... On October 1, 1942, new editions were implemented with a total of 40,000 keys counting both normal and R.P.

... This was meant to avoid providing our opponent with a reusage of keystream, even partial. For that purpose, since a maximum length of 500 letters was prescribed for each message, the external keys, within the total keystream generated by the internal key, had to be distanced by a number of elements greater than 500.

... Unfortunately a fixed number of elements (2497) was prescribed by our planning.

... The books containing the Table of External Keys had a certain number of page, subdivided among the different users, on the basis of the quantity of keys assigned to each user.

Each page contained a number of keys chosen at random, not repeated, among the 40,611 of the general plan. They were listed in rows and columns. The encipher would each time select within the relevant pages the key he was to use and checked it off in pencil to avoid reutilization before checking off all the keys at his disposal. After finishing the encipherment he would place an indicator group as first and last group of the cryptogram. By an appropriate index, he would furnish the receiver page, column, and row numbers pertaining to the key. Obviously with this procedure only to those who had the above mentioned secret books were in a position to interpret the indicator groups, i.e. know the external key used in the messages.

Note: If this system had been properly used, the British wouldn't have been able to decipher any message.

Table 6: Quantities of External Keys assigned to the Differents Commands (March 1942)

| Unit | Normal | RP |

| Supermarina e M.M. | 3500 | 300 |

| Com. FF.NN.e Com 1 Sq. | 500 | 100 |

| Marina Napoli | 200 | 100 |

| Marina Morea | 1500 | 100 |

| Marina Libia | 200 | 100 |

| Marina Tripoli | 1000 | 100 |

| ... | ||

| Reserve | 1700 | 600 |

I wrote an example of using this indicator method. I also created a Table of External Keys and a complete List of Distribution. Finally, I give an example of a used Table of External Keys (with some External keys crossed out).

Netherlands indicator system (World War II)

The operator chooses a wheels setting at random, for two wheels that must be set identically. The key list not only indicates the pin and lug setting but also the two wheels which are identical. For example, on the 3rd July, the wheels 23 and 17 must have the same start setting. An example of a message key which respects this rules : RXFMQF.Then the operator creates the plain indicator by removing the double letter of the message key: RXFMQ. You can see that the plain indicator is five letters long.

Then the operator enciphers the plain indicator at the base setting (Wheels set at AAAAAA). It is assumed (for example) that the result is JWIXE.

Finally, the operator enciphers the message at RXFMQF wheel setting and adds at the beginning and at the end of the message, the five letters enciphered indicator: JWIXE.

This indicator system is not very good because every message key is enciphered at the same base setting. It is even worse, if the operator chooses wheels setting at regular intervals. In consequence, American Intelligence Services were able to read the Dutch messages exchanged between Brisbane and London or Washington.

The Belgium system indicator

In 1960, the Ministry of African affairs in Belgium used the M-209 to cipher her messages. Mr Preneel, in 2001 deciphered some messages from this Ministry and deduced the indicator system used.The 6th wheel was always initialized in the same position as the 5th, then the indicator group was five characters long. Mr Preneel deduced that the Playfair cipher was used to encrypt these external keys. The Playfair key was a random permutation of 25 letters.

Example:

Mr Preneel does not give many details in his article but he described

the whole method in his final report.

The Playfair table:

| G | X | L | N | S |

| K | H | T | W | O |

| Q | D | E | F | A |

| M | V | I | C | R |

| Z | B | P | U | J |

The fifth wheel start (which was the same that the sixth wheel start) is replaced in the indicator by the letter on the left in the Playfair table.

If the External key is "MERFJJ", the Indicator is "IQCAU" ( ME -> IQ, RF -> CA, J -> U ).

Remark: The letter "Y" wasn't used.

The French system indicator for C-36 cipher machine at the WWII beginning

I have not found an official document describing the French indicator system. But, I found a document kept in the military archives offering an improvement of the existing system. This suggests much of the system used. What's certain, it's that there are two indicators groups, the first giving the external key and the second being a confirmation. Four substitution alphabets was used in all, one to encrypt the first group, the others (three) to encrypt the second group. The indicator system is the same for all of the army and for both machines B 211 and C 36. This last point being criticized by the document author and then he proposes an alternative that allows to know the machine used. In any case, the current system is not described in detail, which is why I propose a more complete description plausible but obviously not certain.At the beginning of the 2nd World War, the French were using an indicator system composed of two groups of five letters to convey the external key of cipher machines C-36 and B-211. It was indeed the same indicator system that were used for both machines. The objective is not to reveal to the enemy the cryptosystem used. But actually it was not practical. An cipher clerk was trying to decipher the message on a first machine (eg B-211) and if the result was incomprehensible then he tried on the second machine (eg C-36).

The first indicator group showed the external key, the second was just a confirmation.

Both indicators groups was not placed at the beginning and / or end of the message but burried therein.

The indicator groups doesn't indicate the network. Perhaps the whole Army shared the same internal key?

In the case of the C-36, the first group specified starting position of the five wheels. I think that the slide was part of the Internal key because you need to unlock the machine to set it. Conversely, you don't need to open the C-446 to set the Slide. For this machine, the Slide is part of the external key. The first group was encrypted using a substitution alphabet. The second group specified the same information using a different substitution alphabet selected from three other alphabets. I guess the four alphabets were valid for a specific period (eg one month), and each day a alphabet was used to encrypt the first group. The different alphabets were valid for the entire army.

In the case of the B-211, the external key must specify the starting position of the four wheels comprising respectively 23, 21, 19, 17 pins and the starting position of the two half-rotors each having ten positions. It is possible to encode this external key using the first four letters to encrypt the initial position of the wheels and the last letter to encrypt the rest: the letters A to K to encrypt the position of the first half-rotor and the position of the second half-rotor (they have then the same initial position). the second group confirming the first following the same logic as explained above.

Conclusion: this system is apparently clever, but is not very safe. A simple substitution does not sufficiently mask the key. If one deciphers enough messages, all alphabets can be restored.

The indicator method used by US Army during WWII

The indicator method most used by the US Army during 2nd world war is that described by NF6X. The indicator has the AABCD EFGXY structure: The first letter is doubled. It indicates the use of the M-209. The following six letters correspond to the encrypted message key. The last two letters identify the network. Both groups are present at the beginning and at the end of the message. This method has been used from the beginning of the war, but not necessarily exclusively. Then, particularly during the Korean War, it became the only recommended method and it is described in the 1947 manual TM 11-380. During the second war, the indicator method was described in the SOI along the internal setting of the current month.Is the Enigma system indicator suitable to Hagelin's cipher machines?

The Enigma system indicator is simple: The cipher clerk chooses at random the start position of each wheel. Then he ciphers the External key. Finally, he sets the wheels at the External key and ciphers the message.This method is safe but it isn't better than the US one. Worse, it is necessary to have three Indicator groups (6 letters x 2 + 3 letters for network indicator). Only two five letters groups are used in US method.

Then, there is no raison to prefer it rather than US method.

C.A. Deavours and L.Kruh wrote that if 100 messages of 500 letters was

sent, there are 4% of chances to have an overlap of more than 100

letters.

Excerpt from "Machine Cryptography and Modern Cryptanalysis"

by C.A. Deavours and L. Kruh:

The enemy needs computers to discover these overlaps, but in the period

1960-1980, we can infer that it is the case. During this period, if a poor

organization (an Ambassy of a small country for example), uses the

Italian indicator method, and limits the length of a message to 500

letters, its crypto-system is good even against computers.

In the Italian indicator system, overlaps (messages in depth) can't occur

because a set of messages keys is assigned to each correspondent. After

using a message key, the operator crosses out it so he doesn't reuse it.

The most secure system

The American system (the enciphered one) is very good. During World War

II and Korean War, it insured a very good level of security. But in any

case, it isn't a perfect one.

"The table below show the probability of at least one keying

overlap occuring for messages whose average length is 500

characters (500 was the maximum length generally allowed using

one message key) and varying amounts of overlapping text."

# MESSAGES SENT P(OVERLAP) P(OVERLAP) P(OVERLAP)

(RANDOM KEYS) OVERLAP>100 OVERLAP>200 OVERLAP>300

50 1 % 1 % 1 %

100 4 % 4 % 3 %

150 9 % 8 % 6 %

200 16 % 14 % 11 %

250 24 % 21 % 16 %

300 32 % 29 % 23 %

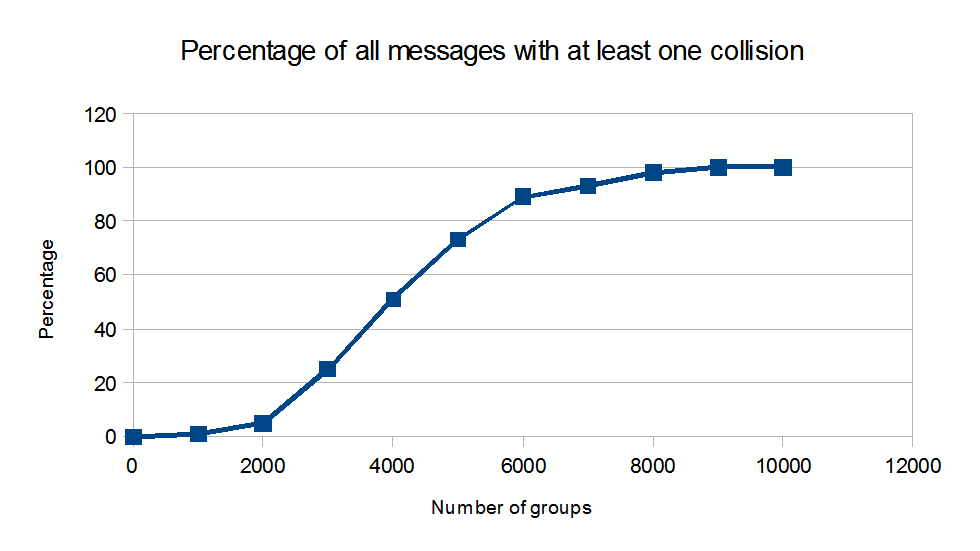

Personally, I simulated generation of messages each one limitted to 500

letters and total length limited to 10,000 groups of 5 letters (the maximum

allowed by the TM 11-380 1947 version). Of course, the wheels start

setting was chosen at random. I found that there are 5% chances

to have at least one overlap of 50 letters with a total of 2000 groups

sent. With a maximum of 8,000 groups there are 100% chances to have at

least one overlap. If the enemy discovers this overlap, he can be able to

read all messages encipered by the internal key.

References

TM 11-380, 1942

HAG KEY LIST, 1942

Formal Aspects of Security, First International Conference, FASec 2002,

London, UK, December 2002, Revised Papers, Springer

See Also, the Diplomatic page of this site.